Who will heal our forests and fields? Smart farmers, that's who!

Published: Sep 30, 2023 Reading time: 8 minutes Share: Share an articleCzech landscape is not well. Although mountain forests are largely healthy, the soil in the lowlands is degraded as it is gradually washed into the rivers. Such a landscape will struggle to resist climate change. We need to start thinking progressively, managing regeneratively and introducing agroforestry practices. Furthermore, we need to realise how much our cities need green spaces.

The health of our forests, meadows and arable land is inherently linked to their altitude: the lower they are, the heavier the anthropogenic impact. The vast, hot Czech lowlands suffer from deforestation, sun, wind, and rain exposure.

Read the first part of our miniseries on landscape health.

The soil of our most fertile and agriculturally valuable areas has been damaged by decades of ploughing, compaction by heavy machinery, and chemical deposition. The widespread drainage for land reclamation has contributed to the drying and weakening of the landscape. The consequences of such activity are reflected in the poor health of the lowland forests. Lowland areas tend to get very hot, because of the absence of vegetation during much of the summer when the fields are barren. As the agriculture becomes more intensive, also the sizes of forest patches decrease, which exposes trees to stress such as drought and strong winds. Such unhealthy trees are then easy prey for bark beetle.

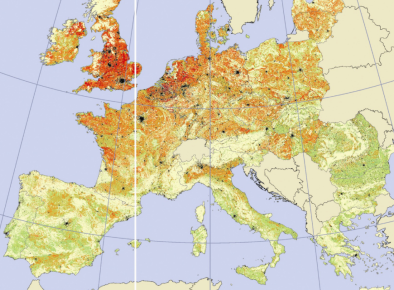

Our interactive infographic shows how healthy the fields in your neighbourhood are, the urban spaces around your house and the coniferous forests you know. Use the drop-down menu to select a landscape type and see how it contributes to landscape diversity and cooling in terms of photosynthesis and biomass production:

Source of land cover classification: Consolidated Ecosystem Layer of the Czech Republic (https://metadata.nature.cz/record/basic/63c80cbb-5824-4895-8651-755a10a020812)

However, despite the problems, solutions are within reach. To fix our landscape, we must bring back native tree species and other features, such as wetlands and floodplain forests. We need to change how we manage the land. We must integrate species-rich crops instead of monocultures and combine annuals and perennials. It is crucial to reverse the trend of soil depletion towards soil restoration. Regenerative farming and agroforestry methods should be applied.

Forests are disappearing in the lowlands but holding on in the mountains

Forests cover 37% of the total area of the Czech Republic and contribute 26% to the landscape's overall health—see part one of this miniseries. Healthy forests are closely linked to higher altitudes. The healthiest and largest forest formation is found in the east, in the White Carpathians and Moravian-Silesian Beskydy. However, unhealthy forests are more likely to be found at lower altitudes.

Forests provide vital ecosystem services: they regulate the climate and the small water cycle, support biodiversity, produce wood and other materials, and provide space for recreation. They are our greatest natural resource and our most valuable contemporary land use.

At the same time, however, the Czech forests are suffering, in particular from conventional management, which emphasises species-poor spruce monocultures instead of natural, predominantly deciduous forests. The current rising temperatures do not benefit spruces, which prefer the cooler and wetter conditions of the Nordic countries. Weakened spruce trees are easily susceptible to drought and bark beetles, resulting in large areas of dying and dry trees, especially around Bruntál and Vysočina (cf. www.kurovcovamapa.cz).

Want to know how the forest in your neighbourhood is doing or how your local farmer is farming? Check the high-resolution outputs for Czech forests and farmland in our app:

https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/21064dca2e84455fbb697b93615b426a/

Is intensive farming sustainable?

Agricultural land occupies 46% of the total land area of the Czech Republic. However, it only contributes 16% to the landscape's overall health. In our study, this land includes permanently grassed areas used for silage and regularly ploughed land used to grow annual and winter monocultures. Our lowlands are characterised by intensive farming, while the number of areas farmed extensively increases with altitude.

Extensive farming includes more grassland, trees, and landscape features, contributing to higher landscape health values. Conversely, intensive farming has some of the lowest ecosystem health values of all land use types, even lower than 'continuous urban fabric – i.e. predominantly built-up areas. Indeed, these urban areas include trees and lawns and are greener on average throughout the year than arable land, which is devoid of vegetation for most of the year (see infographic above).

Conventional farming is built on suppressing the landscape's health through ploughing and pesticides and replacing the natural functions of a healthy ecosystem with industrial fertilisers. Large-scale farming requires a completely uniform landscape, free of obstacles and "pests", which entails the displacement and eradication of other species above and within.

As a result of deforestation and exposure, the soil loses its fertility. It is gradually washed into watercourses and carried away by the wind, a process called erosion.

How to (un)manage for health

The article above underscores why agriculture is now labelled as a sector that does not benefit biodiversity, uses land wastefully and burdens the landscape with agrochemicals. However, this is not always the case, nor necessarily so. Conscious farmers, ranchers, and vignerons who strive to farm harmoniously with nature are examples of gradual change for the better.

These farmers have moved away from monocultures and ploughing. The efforts to maximise yields or excessive doses of fertilisers are long gone. Increasingly, they opt for ecological approaches that respect the landscape and natural processes. They are rediscovering the experience of our ancestors and modern, nature-friendly practices that respond to climate change.

Diverse viticulture to promote a healthy landscape

Modern vignerons, for example, pride themselves on the quality of their products and landscape. In their vineyards, they combine vine plants with strips of deep-rooted herbs. These activities promote humus renewal and the loosening of the soil, which has improved water retention capacity and is less prone to erosion on slopes. Furthermore, such action feeds the edaphon (i.e. the community of soil organisms) and pollinators. In addition, they cool and humidify the air, improving the vineyard microclimate and helping sequester carbon dioxide.

In such diverse vineyards, plant mixtures contain about twelve to fifteen berry-like species that grow and flower gradually throughout the growing season. These are not an infestation of weed species from the surrounding landscape but a purposeful mixture with proportions of individual species appropriate to the site.

Arable land produces approximately 1.2 tonnes of CO2 per hectare per year. However, a vineyard planted this way can reduce these emissions to 0.8 tonnes of CO2 annually. Your car's annual emissions are approximately 4.5 tonnes. Therefore, we could say that by greening a hectare of vineyard, you could off-set 3,000 km of driving.

Urban greenery cools and cleans

Cities provide people with work, play, and living space; they are an integral part of our landscape. In the Czech Republic, cities cover about 5% of the total land area. However, their footprint on the landscape is significant and mostly negative.

Cities suffer from water overdrainage caused by sewage systems, paved surfaces make water infiltration impossible, and urban vegetation is subject to trampling and soil compaction by traffic. Together, these are all causes of the urban heat island effect. Cities warm faster than the surrounding landscape, sometimes up to 4 °C, because they store heat for extended periods, and concrete surfaces cannot cool down—even overnight.

To combat the heat island effect, it is essential to maintain parks and interconnected green infrastructure in cities. Urban greenery provides a place to relax and a slice of nature and can buffer the effects of climate change. Parks and green spaces cool and humidify the environment, retain water, provide shade, clean the air, sequester CO2, and support biodiversity.

We must—and we can—create more green spaces and establish them thoughtfully with environmental benefits in mind. Good establishment starts with choosing suitable plant species (which may be related to the size and shape of the tree canopy, for example) and an excellent growing media and continues with regular maintenance. And then, of course, our urban greenery needs care and respect from us, the city dwellers.

• Landscape Health Index: determines the condition of living structures in terms of their ability to bind solar radiation and species and spatial diversity.

• Ecosystem health: determines the condition of living structures in terms of their ability to bind solar radiation and species and spatial diversity.

• Ecosystem functions: The vital functions (services) that landscapes provide, especially the production of food and materials, climate regulation, and opportunities for recreation and learning.

• Photosynthetic potential: The ability of plants to capture solar radiation. Some of this energy is stored by plants in their leaves, stems and fruits and determines how much crop grows in the field, how much grass grows in the pasture and how much wood grows in the forest.

• Cooling capacity of vegetation: the ability of plants and trees to "cool" by evaporating water from the surface of their leaves (transpiration). The greater the ability to cool, the healthier the ecosystem.

• Landscape diversity: the number of species of animals and plants, the variety of habitats for organisms, and the age and spatial diversity of trees and vegetation. It is the opposite of the homogeneous landscape created by conventional agriculture.

• Potential natural vegetation: Used to estimate the potential vegetation cover that would spontaneously form if humans 'disappeared' from the landscape or ceased farming altogether.

• Agroforestry: An agricultural system that mimics a forest ecosystem. Farms that mimic natural, diverse communities are more productive, resilient to extremes, and less costly than conventional farming (no-till, pesticides, fertilisers).

• Regenerative farming: Growing annual plants together with intercrops, without ploughing or applying artificial fertilisers. The farmer aims to gradually increase the health of the soil by accumulating humus and strengthening the species diversity in the soil, thus saving on ploughing, fertiliser, and pesticides.

How healthy is specific Czech region? Read the second part of our miniseries about the health of Czech landscape!