Think the Czech landscape is healthy? Think again!

Published: Sep 20, 2023 Reading time: 9 minutes Share: Share an articleThe Czech landscape is in a poor state. Using satellite imagery, we have assessed its condition, and the results speak for themselves. Soil is dying, trees are declining, water is disappearing, and temperatures are rising. This sad state of affairs is primarily caused by conventional farming. Modern farming has caused deforestation, a decline in biodiversity, and soil erosion. If we want our landscapes to continue to nourish us, to provide us with a refuge or simple beauty to relax in, we need to act. In this article— the first of our three-part miniseries—we talk about the overall potential of our landscape.

The health of a landscape directly corresponds to the health of its inhabitants—people, animals, plants and micro-organisms. Landscape health expresses the diversity and the extent to which the landscape matches its potential in terms solar energy captured by photosynthesis and vulnerablility to natural and man-made disasters. It is a crucial parameter determining the ability of a landscape to maintain suitable conditions to support its inhabitants. However, today, our landscape is not in good health and we owe a debt not only to it but to future generations.

Our landscape is far below its potential

The landscape in the Czech Republic is marred by inadequate management, particularly in the fertile floodplain areas around the Elbe and Morava rivers. The interactive map shows how different parts of our country are faring.

You can see how different parts of Czech country are doing in the interactive map.

Plants are a crucial element of our landscape because of their capacity to capture solar energy. Why is this important for us? Plants capture sunlight in two ways. By photosynthesis and cooling the landscape, plants use some of the sun's energy to convert water into steam (transpiration). However, our research shows that a significant portion of the sun's radiation remains unused by our landscape, as a large part of our country lacks vegetation for a considerable part of the year. This is a problem twice over.

1) Our management of the landscape is inefficient because the landscape’s full potential is not being realised. A significant amount of energy is being wasted. This energy could be used to produce biomass, oxygen, landscape cooling, or for sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

2) Unused solar energy is converted into harmful heat, contributing to overheating of the landscape, drought, loss of soil fertility and generally uncomfortable living conditions for both people in cities and the countryside.

The high degree of landscape homogenisation has also reduced the abundance of animals and plants and the overall diversity of landscape features (such as woods, alleys, poolsponds, etc.). This reduces attractiveness and ecological stability, making the landscape less able to withstand the effects of extreme weather.

The Czech Republic's Landscape Health Index is 49%, below half of its potential.

Interactive map

Do you want to know how healthy are the regions or municipalities in the Czech Republic? You can find out on our web map and see examples of good and bad practices in landscape management:

https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/95d3325311fb4b8e9926f1e7341a3813/

From mixed forest diversity to agricultural desert

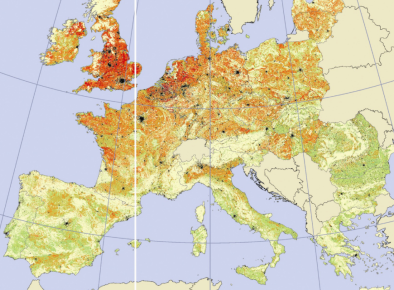

In our assessments, forest-covered mountainous areas, such as the Beskydy and Šumava, came out as the healthiest and represent our most valuable natural assets. In fact, forested areas provide the most ecosystem functions and services—these are so-called multifunctional landscape uses. Forests are found in almost 40 % of our country contributing to the overall health of the Czech landscape in one quarter. The Czech landscape belongs to a biome type known as 'mixed temperate forest', so the forest is intrinsically part of it and will naturally try to return to this state (Figures 1 and 2). Unfortunatly, human activities disrupt this process in every way possible through clearing, regular ploughing and the use of chemicals. Our activity has several negative impacts on the landscape: the breakdown of remaining forests; the loss of soil fertility; and the creation of large heat islands.

Arable land, the dominant agricultural land component, produces only food and fodder and is, therefore often a mono-functional type of landscape use. Although agricultural areas occupy almost half of the Czech landscape, they contribute only 16 % to its total health. They do not cool the landscape (quite the contrary), are not aesthetically valuable, do not serve for recreation and do not provide a home for numerous species of plants and animals.

Over the centuries, forests were gradually cleared, and large agricultural areas were created in the fertile areas of the Elbe and Morava rivers, which gradually swallowed up the remaining islands of vegetation. Forests and wetlands have been replaced by annual monocultures, which today form large continuous areas.The landscape has continued to change. The original mixed forests have been replaced by spruce monocultures, which are now the dominant forest type. With mechanisation in agriculture and forestry, watercourses have been straightened and reinforced, meadows and copses ploughed, and wetlands drained.

Health of Czech forests, fields, meadows, and settlements

Humans use the landscape in several different ways. These vary significantly in how they contribute to the overall health of the landscape, its diversity, fertility, and cooling capacity.

Bohemian forest ecosystems capture the most solar radiation during photosynthesis and are the most important landscape type in terms of cooling. They are also the most diverse type of landscape cover, but a significant part of these lands consists of monocultures. Parts of our forests are arid and do not grow. They are suffering from the effects of bark beetle infestation and the effects of intensive harvesting (clear-cutting).

Grasslands are areas with a predominance of grass that are natural and not primarily used for grazing or hay production. They play a role in maintaining a varied landscape mosaic and are mowed as necessary to keep them from becoming overgrown with woody plants. They are often located in mountainous, dry or wet places, and protected areas, i.e. places unsuitable for agriculture. In our survey, grasslands scored lower than forest ecosystems because they represent a more homogeneous landscape cover and have only one vegetation layer, unlike forests.

Urban systems are surfaces with permanent vegetation in combination with paved surfaces and buildings. There are so-called continuous and discontinuous urban development and other areas. Urban areas account for 10 % of the total area of the country. They contribute relatively little to the health of our landscape.

Agricultural ecosystems are among the less valuable types of landscape use. They are less than half the value in all respects—even the photosynthetic potential, which corresponds to the annual production of biomass (food, feed and intercrops), is lower than that of urban surfaces. Conventional agriculture practices are based on short-term, intensive cultivation of annual or winter monocultures. For most of the year, the fields are either bare; part of the year, the plants are small and do not cover the soil sufficiently, and part of the year, the crops are mature and de facto dry. For a substantial part of the year, high amounts of solar energy are available but not used by any plants, reaching the soil surface and killing soil micro-organisms, turning the unused radiation into heat and contributing significantly to the overheating of the landscape.

Landscape cover was classified according to the Consolidated Ecosystem Layer: https://webgis.nature.cz/publicdocs/opendata/kves/Konsolidovana_vrstva_ekosystemu_2022_popis.pdf

Can we help fulfil the potential of our landscape?

With the density of the human population, we cannot return to the natural state, but we can manage smarter and take inspiration from nature. One solution is agroforestry, which mimics diverse forest communities. This farming makes the landscape more productive and beautiful and results in significant savings for the farmer in the costs of pesticides, fertilisers and ploughing. Where agroforestry is inappropriate, farmers can apply regenerative agriculture, which seeks to keep the soil surface consistently covered with green vegetation, does not disturb the soil by ploughing and does not use artificial fertilisers.

We measured the current health of the landscape as the distance from a hypothetical ideal situation in which only the healthiest forests and grasslands, which came out as the best in our measurements would cover 100% of our country. At the same time, it is the distance from a hypothetical worst-case situation in which the entire country would be covered by bare land (0%), that defined the worst cases in our assessment.

We assessed the health of the landscape using satellite imagery of the country, taken in 2020 and 2021, and calculated three indicators representing vegetation health (water areas were not included):

A) Photosynthetic potential: the ability of plants to capture solar radiation during photosynthesis;

B) Cooling capacity of vegetation: the total annual number of degrees Celsius by which plants have reduced surface temperature compared to a non-vegetated surface;

C) Landscape diversity: the species, age, and spatial diversity of vegetation. It is the opposite of monotonous use types such as fields or continuous urban fabric

By calculating the average value of the three indicators above, we created:

D) An overall Landscape Health Index includes productivity and diversity of vegetation, the ability to draw water from the soil, and cooling.

Link to the description of the methodology:

Jakub Zelený, Daniel Mercado-Bettín, Felix Müller, Towards the evaluation of regional ecosystem integrity using NDVI, brightness temperature and surface heterogeneity, Science of The Total Environment, Volume 796, 2021, 148994, ISSN 0048-9697

• Landscape Health Index: determines the condition of living structures in terms of their ability to bind solar radiation and species and spatial diversity.

• Ecosystem health: determines the condition of living structures in terms of their ability to bind solar radiation and species and spatial diversity.

• Ecosystem functions: The vital functions (services) that landscapes provide, especially the production of food and materials, climate regulation, and opportunities for recreation and learning.

• Photosynthetic potential: The ability of plants to capture solar radiation. Some of this energy is stored by plants in their leaves, stems and fruits and determines how much crop grows in the field, how much grass grows in the pasture and how much wood grows in the forest.

• Cooling capacity of vegetation: the ability of plants and trees to "cool" by evaporating water from the surface of their leaves (transpiration). The greater the ability to cool, the healthier the ecosystem.

• Landscape diversity: the number of species of animals and plants, the variety of habitats for organisms, and the age and spatial diversity of trees and vegetation. It is the opposite of the homogeneous landscape created by conventional agriculture.

• Potential natural vegetation: Used to estimate the potential vegetation cover that would spontaneously form if humans 'disappeared' from the landscape or ceased farming altogether.

• Agroforestry: An agricultural system that mimics a forest ecosystem. Farms that mimic natural, diverse communities are more productive, resilient to extremes, and less costly than conventional farming (no-till, pesticides, fertilisers).

• Regenerative farming: Growing annual plants together with intercrops, without ploughing or applying artificial fertilisers. The farmer aims to gradually increase the health of the soil by accumulating humus and strengthening the species diversity in the soil, thus saving on ploughing, fertiliser, and pesticides.

How are the individual regions of the Czech Republic doing? Which is the healthiest and why? Find out in the next instalment: